I don't often read poetry, but on Robin Sloan's recommendation I picked up "Nineteen Ways of Looking at Wang Wei" by Eliot Weinberger and was delighted.

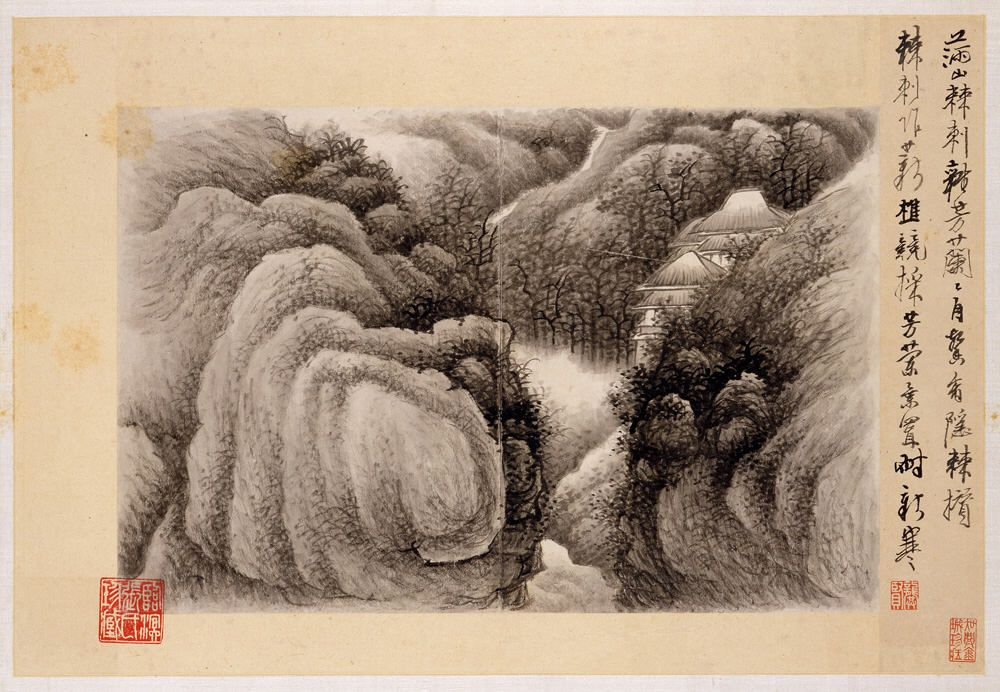

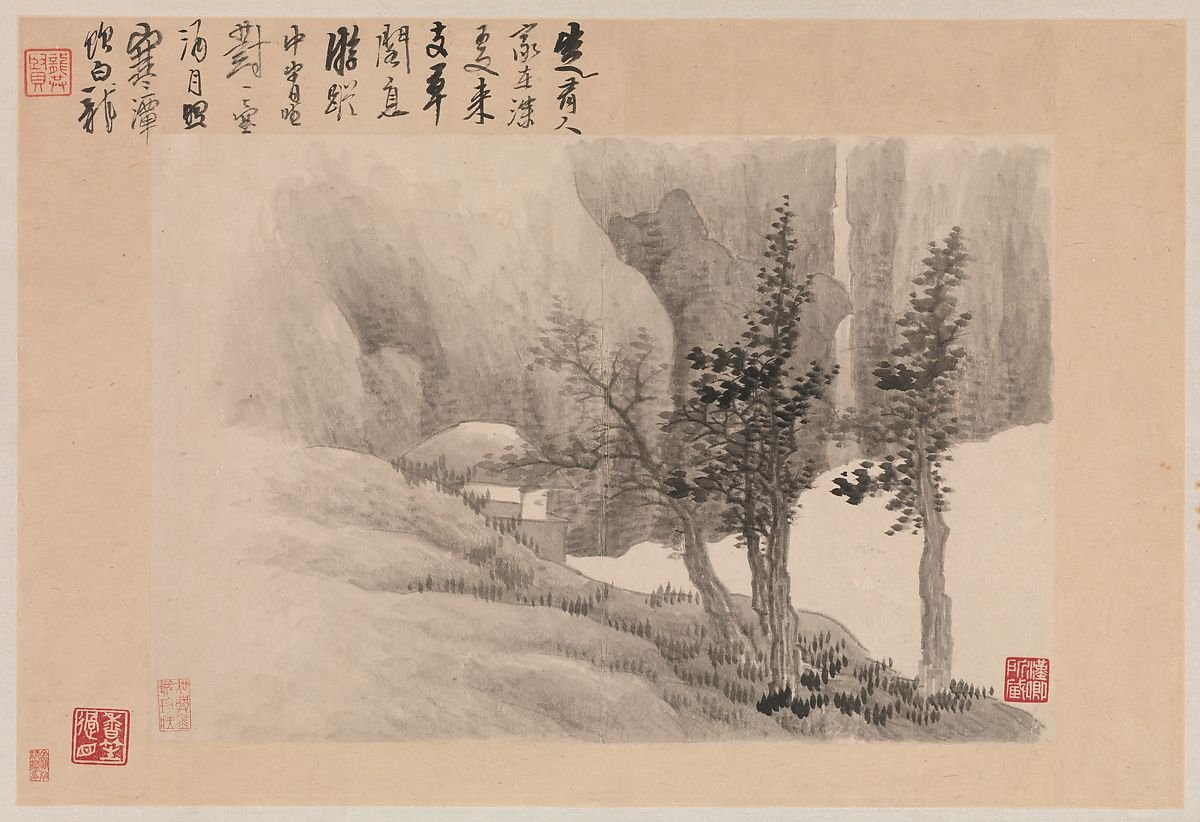

The eponymous Wang Wei - a wealthy buddhist painter and calligrapher - wrote a series of twenty scroll poems around the 700s. (You may have seen these before, so closely are they associated with Chinese art in general). Of those twenty, one - Lu Zhai or Deer Grove - is the foundation for this short book about translating a poem in 19 different ways. 1

But before jumping in, I want to talk about translation more broadly. Have you thought about it lately? Or ever?

I didn't, at least not before reading "The Translation Wars" by David Remnick about the histories of translating Tolstoy and Dostoevsky into English.

Therein, a scathing barb about Constance Garnett – Victorian lady, prodigal translator, and one of the earliest translators of much of the body of classic Russian literature – stuck with me for a long time: “The reason English-speaking readers can barely tell the difference between Tolstoy and Dostoevsky is that they aren’t reading the prose of either one. They’re reading Constance Garnett,” wrote a sour Joseph Brodsky. 2

But not all translations are poor-man's copies: Gabriel Garcia Marquez once said that he liked Gregory Rabassa's English translation of 100 Years of Solitude better than the original.

Then there is Haruki Murakami, who doesn't read his own works in translation, but grew up with so much English-literature as an influence that he "wrote the opening pages of his first novel, Hear the Wind Sing, in English, then translated those pages into Japanese, he said, 'just to hear how they sounded.'" Just think: a book that is a translation at conception, translated as it is being written. 3

Others – Vladimir Nabokov in particular – have chosen to bypass the perils of translation by writing and translating their own books. And writing in a foreign language is liberating! The language of Lolita was born out of that freedom. Just consider the play of its first lines:

Lolita, light of my life, fire of my loins. My sin, my soul. Lo-lee-ta: the tip of the tongue taking a trip of three steps down the palate to tap, at three, on the teeth. Lo. Lee. Ta. She was Lo, plain Lo, in the morning, standing four feet ten in one sock. She was Lola in slacks. She was Dolly at school. She was Dolores on the dotted line. But in my arms she was always Lolita.

Or consider English writer Jumpa Lahiri on that same freedom, except in this case leaving English for Italian:

By writing in Italian, I think I am escaping both my failures with regard to English and my success. Italian offers me a very different literary path. As a writer, I can demolish myself, I can reconstruct myself. I’m bound to fail when I write in Italian, but, unlike my sense of failure in the past, this doesn’t torment or grieve me.

Other languages, other worlds.

But back to Wang Wei and his classical Chinese scroll poem.

According to Eliot Weinberger, the challenge of translating classical Chinese is that:

Chinese has the least number of sounds of any major language. In modern Chinese a monosyllable is pronounced in one of four tones, but any given sound in any given tone has scores of possible meaning. Thus a Chinese monosyllabic word (and often the written character) is comprehensible only in the context of the phrase: a linguistic basis, perhaps, for Chinese philosophy, which was always based on relation rather than substance.

So that precludes what we think of as "Western" poetry, which grew to rely on rhyme and meter first as a mnemonic device and later as a literary flourish. Weinberger continues:

Of particular difficulty to the Western translator is the absence of tense in Chinese verbs: in the poem, what is happening has happened and will happen. Similarly, nouns have no number: rose is a rose is all roses.

With that in mind, it's interesting that the modern birth of Chinese poetry in English came from much the same time and place as the birth of Modern poetry in English broadly: with Ezra Pound. His Cathay, published in 1915, was for most people the first introduction to Chinese poetry.

More interesting still, Weinberger notes that Pound didn't actually know Chinese – he "intuitively corrected mistakes [in earlier] manuscripts." And yet, "Pound's genius was the discovery of the living matter, the force, of the Chinese poem – what he called 'the news that stayed news'."

Just consider the following two poems:

In a Station in the Metro

The apparition of these faces in the crowd:

Petals on a wet, black bough.

Ts’ai Chi’h

The petals fall in the fountain,

the orange-coloured rose-leaves,

Their ochre clings to the stone

Written by an avant-guard European writer at the turn of the 20th century or plucked from the annals of Old Chinese Poetry?

Yet the influences ran both ways. What for Pound was an intuitive understanding of what Chinese-as-a-language afforded to poetry by way of breaking with Western poetic tradition, "Chinese poets were, however, excited by the doings in the west. Hu Shi's 1917 manifestoes, which launched the 'Chinese Renaissance' in literature by rejecting classical language and themes in favor of vernacular and 'realism', were largely inspired by Ezra Pound's 1913 Imagist manifestoes." Here's Hu Shi:

The Night of January 24th

The shadow of the aged pagoda tree,

Is gently waving in the moonlit ground;

A few dry leaves are still dancing on the date tree,

To make a feeble voice from time to time.

The autumn tint of West Hill beckons me several times,

Unfortunately I am shackled by my own disease.

Now they say I am to be well.

And the remotely gorgeous autumn is long past.

So more ironic still is the thought that Wang Wei's poetry was once just as fresh and real and perhaps even vernacular in its time. It is the classicists that hold it back: what we might think of as a calcified language stuck in history simply requires its own translation from past to present.

In that sense, translation from one language to another affords us a fresh view of a literary work, one that doesn't need to be stuck in the past. In English, only Chaucer and Shakespeare seem to have made that leap, from Olde English to modern ears.

But right. Wang Wei's poem itself! Here is it in the original:

Translated literally, word by word, the poem could read as follows:

Deer Park

Empty, mountain(s)/hill(s), (negative), to see, person/people

But, to hear, person/people words/conversation, sound/to echo

To return, bright(ness)/shadow(s), to enter, deep, forest

To return/again, to shine/to reflect, green/blue/black, moss/lichen, above/on/top

From there begins Weinberger's humble exploration, pointing out baggage that later translators brought to Wei, the way that Constance Gartner turned Tolstoy and Dostoevsky into minor Dickenses. Of translator's changes, Weinberger considers them vandalous acts of "needing to explain and improve" the poem.4 Consider the following mutations:

On W.J.B. Fletcher's 1919 translation:

"Where Wang's sunlight enters the forest, Fletcher's rays pierce slanting".

Or G. Margoulies' (1948):

He "prefers to generalize Wang's specifics... nobody in sight becomes the ponderous malaise of everything is solitary."

Or Chang Yin-nan & Lewis C. Walmsley (1958):

"In this poem, couplets are reversed for no reason. The voices are faint and drift on the air. The mountain is lonely (surely a Western conceit, that empty = lonely!), but it is a decorator's delight: the moss is as green as jade and sunlight casts motley patterns... It never occurs to Chang and Walmsley that Wang could have written the equivalent of casts motley patterns on the jade-green mosses had he wanted to. He didn't."

Others still transform see into meet (Chen & Bullock, 1960) or introduce rhymes: "the 19th century resound is only there to rhyme with ground" (Liu, 1962). Others still seem to do what they want: Kenneth Rexroth (1970) "ignores what he presumably dislikes, or feels cannot be translated" while H.C. Chang (1977) "translates 12 of Wang's 20 words, and makes up the rest".

Weinberger also points out that "contrary to evidence of most translations, the first-person singular rarely appears in Chinese poetry [...] the experience becomes both universal and immediate to the reader." Yet translators take various liberties in inserting a narrator into poem. On Fletcher again: "Where Wang simply states that voices are heard, Fletcher invents a a first-person narrator who asks where the sounds are coming from." Worse still is G.W. Robertson (1971) with the line We hear voices echoed: "Robertson not only creates a narrator, he makes it a group, as thought it were a family outing. With that one word, we, he effectively scuttles the whole mood of the poem."

Weinberger considers there to be few translations with fidelity to the language and spirit of the poem: "The taxonomy of Chinese translators is fairly simple. There are the scholars: most are incapable of writing poetry, but a few can. And there are the poets: most know no Chinese, a few some."

Of the nineteen the he examines, two stand out to me as bridging that gap. First is Burton Watson's 1971 "Deer Fence":

Empty hills, no one in sight,

only the sound of someone talking;

late sunlight enters the deep wood,

shining over the green moss again.

and Gary Snyder's 1978 take:

Empty mountains

no one to be seen.

Yet–hear–

human sounds and echoes.

Returning sunlight

enter the dark woods;

Again shining

on the green moss, above.

Wang Wei's poem is evocative without the need for embellishment, even if separated from its original painting. Likewise, these translations avoid the "empty parody of Eastern Wisdom: in an empty glass there is no water", as other translstions seem to introduce ("In empty mountains no one can be seen", afforded to us by a clumsy William McNaughton (1974)). These two retain the simplicity and directness of the original, their variations adding less the voice of the translator and moreso exploring the differences that the original Chinese words could have implied. There is room in the literature for both.

Still, if Weinberger's brief account leaves me with any thoughts, it's less on the beauty of Wang Wei's poetry, and more on the renewed awareness that when reading in translation, you should be mindful of when you are reading the writer... or reading the translator.

But as Remnick notes, short of being bilingual, we are

left adrift on our various linguistic ice floes, only faintly hearing rumors of masterpieces elsewhere at sea. So most English-speaking readers glimpse Homer through the filter of Fitzgerald or Fagles, Dante through Sinclair or Singleton or the Hollanders, Proust through Moncrieff or Davis, García Márquez through Gregory Rabassa—and nearly every Russian through Constance Garnett.

... or Wang Wei through 19 different filters.

End Notes

1 - While the original poems are lost, they're remembered through existing copies that date as far back to the 1700s - "Wang's landscape after 1000 years of transformation" as Weinberger puts it.

2 - Later that week I made my way to the nearest Barnes and Nobles (alas, high school in suburbia!) and picked through the 3 different translations of Crime and Punishment, reading them side by side to see which one I liked better and what those differences were. The Pevear & Volokhonsky if you're going for Dostoevsky or Tolstoy, but I didn't much like their Master & Margarita or Dr. Zhivago, if you must know.

3 - Murakami is an interesting fellow. He was also a translator who worked on Raymond Carver and F. Scott Fitzgerald (which undoubtedly informs his writing), and also collaborates with translators/encourages translators to make 'adaptations'. https://www.nippon.com/en/column/g00144/

4 - The challenge lies between staying true to the language, to the intention, or to the feeling of the poem. For example, in "Translation Wars" referenced earlier, Remnick writes about Vladimir Nabokov's work on Pushkin's "Eugene Onegin" – one of the most famous poems in the canon of Russian classics. Nabokov's translation "is both tribute and apology". He himself wrote in his introduction, "It is hoped that my readers will be moved to learn Pushkin’s language and go through EO again without this crib."

But the particulars within a language confound: here's Nabokov again on a particular turn of words that in Russian makes sense, but in English doesn't:

In translating slushat’ shum morskoy (Eight:IV:11) I chose the archaic and poetic transitive turn “to listen the sound of the sea” because the relevant passage has in Pushkin a stylized archaic tone. Mr. Wilson may not care for this turn—I do not much care for it either—but it is silly of him to assume that I lapsed into a naïve Russianism not being really aware that, as he tells me, “in English you have to listen to something.”

Such is the same challenge with Wang Wei's poem.

Thanks for reading

Useful? Interesting? Have something to add? Shoot me a note at roman@sharedphysics.com. I love getting email and chatting with readers.

You can also sign up for irregular emails and RSS updates when I post something new.

Who am I?

I'm Roman Kudryashov -- technologist, problem solver, and writer. I help people build products, services, teams, and companies. My longer background is here and I keep track of some of my side projects here.

Stay true,

Roman