Originally posted on Error States as "Preserving Digital Media."

In A *New* Program for Graphic Design, David Reinfurt recounts a trip he made to MIT while researching the work of Muriel Cooper, an artist and researcher who's work spanned neatly spanned the analog commercial production of art with early digital production:

We proceed by visiting the MIT Media Lab, where Muriel Cooper spent the last years of her working life, from 1985-1994, continuing the work of the Visible Language Workshop. I'm here to meet a graduate student who's procured a LaserDisk which includes some of the last work of the Workshop. With LaserDisk in hand, we spend the next hour or so trawling various sub basements of the Media Lab building searching for an analog LaserDisc player capable of playing the 20-year-old media format. As we enter more than one room containing stacks of outdated hardware, too difficult to repair, and rotting magnetic-tape formats whose chemical clocks are ticking, I am struck by the ways in which this recent past becomes so quickly inaccessible in a digital medium. In start contrast to the piles of posters that provide a visceral record of the Center for Advanced Visual Studies, these dead media provide nothing tangible. (As much of Muriel Cooper's most important work was in a digital medium, I become more convinced that accounting for her work is critical - now.) 1

20 years for obsolescence to set in, in an archive.

Others are not so lucky. Here's Reinfurt again, now describing the Tetracono by Bruno Munari. It's a small-run piece of "time based" art that changes as you watch it. Reinfurt set out to find a working copy, and has come across it at an archivist's storage:

We unpacked it, but we couldn't find the power cord. The archivist found it a bit later that evening, plugged it in, started it up, and sent me a video. What I noticed immediately was that the Tetracono was running, yes, but, based on everything I had uncovered, it was running incorrectly according to Munari's program. [...]

On returning, we confirmed the fact that it was, in fact, counter to the way that Munari had intended. The archivist had been working with the foundation for a long time and was involved when this Tetracono had been "renovated" about 14 years earlier for a show at the Museo del Novecento. [...]

She knew the person who worked on it and called him. He's retired since, but his workshop exists and between them they decided, yes, this should definitely be corrected. Three months later, the Tetracono was fixed and is now running correctly. So my design research project then accidentally became a historic preservation project. 2

Why bring this up? Much of our known history is told through artifacts that we have left behind. Object and records are preserved -- sometimes intentionally through safekeeping in Museums and collections, sometimes accidentally by being lost or buried, sometimes entirely unintentionally such as clay cuneiform tablets that were preserved by the act of razing villages and cities.

There's a drift that comes with time. I remember walking through the British Museum in London and being struck by a collection of beautiful objects that were more than 4000 years old, about which we know very little. Who made it? What was it used for? Many times, we can only speculate.

Culture and ideas are not too different. Here's architect Jimenez Lai on such drift:

Our customs, costumes, habits, habitations, and manners are abstractions that make up civilization. The practical functions of many human activities grow obsolete from their original intentions with every new generation. Nevertheless, they are abstracted and cherished. Rituals are records of what we once considered beautiful. 3

In Japan, the aging of objects and exploration of their imperfections is reflected in the culture of production. Wabi-sabi, mono no aware, and other aesthetic concepts not only drive how things are made, they also implicitly hint at the longevity and accumulation of future-heritage of these objects:

The works was to be picked up, used, and thus in some way brought to life. Over time, and with everyday use, their appearance inevitably changes. Discolorations and traces of heat and humidity become visible, and with them the memory of the mutability, imperfection, and impermanence of all existence in the world. [...]

Their works are always functional, yet they sometimes seem like art objects too, which is not a contradiction in terms. A separation between applied and "pure" art, between art and craft, did not exist in Japan for a long time. 4

Digital media is in many ways the opposite of future-facing/time-tested craftsmanship. Digital media is haunted by its rot and obsolescence in the way that strictly physical objects are not.

There are two kinds of digital media. One is digital media that has a physical embodiment. The other is the realm of the purely digital.

It goes without saying that physically embodied things degrade. Things are designed to degrade. But digital media's degradation leaves no trace of the original content, just a useless container for what was. Reinfurt's LaserDisks is an example. Vinyl get scratched and becomes unplayable, unreadable. Tapes melt into tree sap.5 Batteries lose their charges and can't power their cases anymore. Powercords are lost. Magnetic tapes get erased. The original strips of card-powered programming tear, get eaten away by bugs, become dust. The players get lost and cannot read the content.

We are left with sentimental husks of plastic and metal - the treasure box but not the treasure.

On the other hand, there is the realm of the purely digital. Programs, code, ideas. For most of recorded history, ideas were recorded in books and on parchment and in stone, or carried on through oral traditions. Today, the greatest volume of these are stored on servers -- still physically embodied, but for the most part abstracted away for the bulk of us.

With that in mind, it is susceptible to bit rot (data degradation). Consider the following:

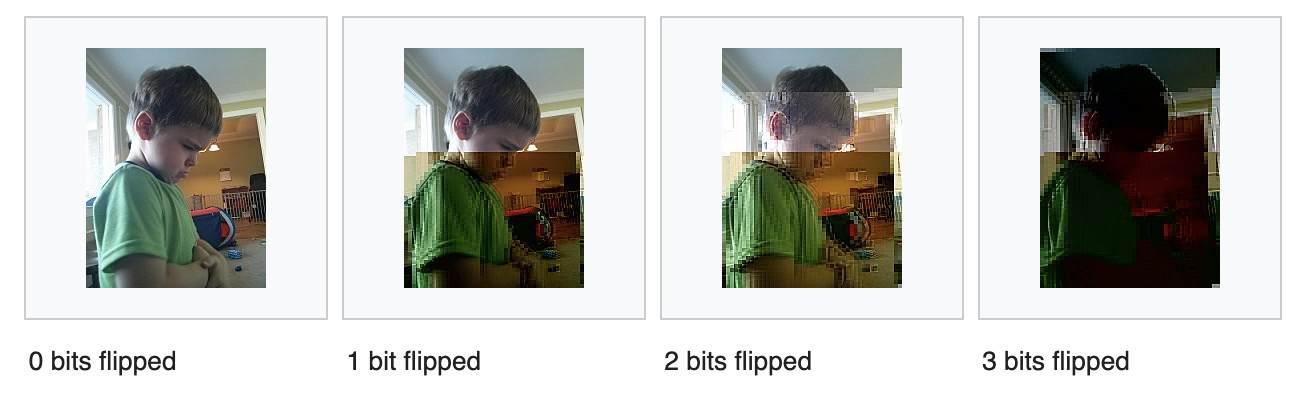

An image file has thousands upon thousands of bits. The image above is 378kb - tiny compared to an average photograph, rather large for web purposes. That's 378,000 bits. Just 3 bits changed and the image is not just unrecoverable... it is garbage.

Wikipedia, helpful as ever, lists 4 types of bit rot:6

- Solid-state media, such as EPROMs, flash memory and other solid-state drives, store data using electrical charges, which can slowly leak away due to imperfect insulation. The chip itself is not affected by this, so reprogramming it approximately once per decade prevents decay. An undamaged copy of the master data is required for the reprogramming.

- Magnetic media, such as hard disk drives, floppy disks and magnetic tapes, may experience data decay as bits lose their magnetic orientation. Periodic refreshing by rewriting the data can alleviate this problem. In warm/humid conditions these media, especially those poorly protected against ambient air, are prone to the physical decomposition of the storage medium.

- Optical media, such as CD-R, DVD-R and BD-R, may experience data decay from the breakdown of the storage medium. This can be mitigated by storing discs in a dark, cool, low humidity location. "Archival quality" discs are available with an extended lifetime, but are still not permanent. However, data integrity scanning that measures the rates of various types of errors is able to predict data decay on optical media well ahead of uncorrectable data loss occurring.

- Paper media, such as punched cards and punched tape, may literally rot. Mylar punched tape is another approach that does not rely on electromagnetic stability.

I'm tempted to add compression as another, intentional form of bit rot. Once compressed, the original is unrecoverable. Things can only shrink.

Of course, there's more than just plain 'rot' that happens. My parents spent many years working as database architects and administrators. I grew up listening to much shop talk about failed data migrations, lost transactions due to improperly implemented code, lost or deleted backups, optimizations that went wrong, sync processes that went out of sync, and the arduous process of fixing those messes day in and day out.

Most people don't see those issues because they're corrected by the time you log in to an app. But not always. I recently had a scare where my blog's server went down and I realized my backups were on the same server as the original files. If anything happened to the server -- a level I had abstracted away in my mind, but was painfully always present -- I would lose both with no recourse. 7

And if you're not in control of your platforms, you're often not in control at all. One must always be thoughtful of the tools you're using. For example, I ran an out-of-the-box WordPress blog for many years. I would upload photos to show to people -- and assuming that my blog was backed up and that saving things on the internet is better than on a computer that had little space and fragile hard drives, I would delete the original images. It wasn't until much later, when I was trying to rebuild my archives, that I discovered that WordPress had automatically compressed my images -- a trade off of quality for performance. There was no way to recover my original images.

Or consider the following, more terrifying example:

Lightroom App Update Wipes Users’ Photos and Presets, Adobe Says they are ‘Not Recoverable’

This morning, multiple readers wrote in to alert us to a major Adobe gaffe. It seems the latest update to the Lightroom app for iPhone and iPad inadvertently wiped users’ photos and presets that were not already synced to the cloud. Adobe has confirmed that there is no way to get them back. [...] This was followed by replies from other users saying that the same thing happened to them, whether or not they were subscription based or free. One user posted to Reddit’s r/Lightroom subreddit saying that they had lost “2+ years of edits” after the update.8

This doesn't even begin to recount proprietary file formats that are no longer supported and thus unopenable, or services that have shut down on the internet. Remember Geocities or Tripod blogs? Vibrant yahoo forums? 'Like tears in the rain,' as Roy Batty puts it.

Going back to data center for a moment, the industry has come a long way since someone stored a single server somewhere that was the mainframe. Multi-zone availability, different types of syncing, quests to perfect synchronization have yielded very interesting technical developments. Heck, Google had to invent a new concept of time in order to manage its worldwide Spanner database.9 Meanwhile, Microsoft is storing its data center underwater and filled with dry nitrogen to account for both energy savings and data loss. After two years underwater, "our failure rate in the water is one-eighth of what we see on land,” Microsoft reported.10

Surely better than a book would have fared underwater, but better than the Antikythera mechanism, the prototypical computer?

I'm often reminded of "Can Neuroscience Understand Donkey Kong, Let Alone a Brain?", research that pointed out that our techniques for understanding brains by looking at the hardware are woefully inadequate analogues for understanding similarly complex digital processes by looking strictly at their circuit boards.11 If a data center goes down, what do we understand from the circuit boards? Are the programs -- stored as electron charge configurations -- readable through any form of technical, reconstructive archeology?

The oldest recorded audio recordings -- dating back to 'phonautographs' in the 1850s -- were recently reconstructed with some pretty clever physics:

Now, what that means is just that someone is standing in front some kind of a funnel and speaking, shouting, singing - we don't know doing what - into that funnel. It vibrates a little membrane, and that wiggles a stylus that scratches this wavy line on a sheet of paper.

[...] They've been working on developing optical message for playing back early sound recordings on delicate media such as, you know, wax phonograph cylinders and so on. The idea being that since nothing is touching the groove except light, there's no wear and tear on the original as there would be if you try to use a traditional stylus or a needle. So adapting that technology to play back a wavy line on a piece of paper was really pretty straight forward. In fact, it may have been simpler because we're just dealing with two dimensions. 12

Similar methods were used for reading scrolls burnt in Pompeii, and older scrolls from biblical times: too fragile to unroll, x-rays and AI were used to virtually unravel and color-contrast the inks form the paper:

“Although you can see on every flake of papyrus that there is writing, to open it up would require that papyrus to be really limber and flexible – and it is not any more,” said Prof Brent Seales, chair of computer science at the University of Kentucky, who is leading the research.

Seales and his team have previously used high-energy x-rays to “virtually unravel” a 1,700 year old Hebrew parchment found in the holy ark of a synagogue in En-Gedi in Israel, revealing it to contain text from the biblical book of Leviticus. 13

Very few people want to think that the work we've made could be lose-able, especially in so short a period of time. Would similar methods -- some sort of spectrometer, perhaps -- be useful one day for reconstructing solid state hard drives after we've moved so far past them, and not continually replicated the data onto new mediums?

And what of the Voyager messages, sent through space in the 70s with then-cutting edge technology?14 Hoping to be recovered by... distant travelers? Aliens? And when found... how will they be read, understood? If someone uninformed found it on earth, even today -- would they know what to do with it, how to read it, how to listen to it? Or at just past 50 years, is it as barely decipherable as biblical tablets and burnt papyrus scrolls?

Endnotes

1 - "A *New* Program for Graphic Design" by David Reinfurt, 2019, Pg 60-61

2 - Ibid, Pg 215-216

3 - "Citizens of No Place" by Jimenez Lai, 2012, Pg 22

4 - "Craftland Japan", Pg 8-9. There's a forthcoming book about the "encrapification" of American production that reads as the diametric opposite of this philosophy. You can find an excerpt here, "The long, golden age of useless American crap":

The encrappification of America dates back centuries. While there were, undoubtedly, once village blacksmiths who forged brittle nails, farm women who adulterated their butter, and tailors who cut corners, these were the exceptions. Most things were made by skilled and reputable hands working with good intentions, supplying the needs of people within local communities. The consumer revolution, which began in the mid-1700s, changed all that.

This lessened the burdens of ownership itself: now easily discarded and just as easily replaced, possessions no longer had to be painstakingly cared for. The marketplace of crap turned a broken kettle or cracked dish from a crisis into a mere inconvenience effortlessly—and pleasurably—ameliorated by a new purchase.

5 - Consider this hilarious [to me] account of "baking" tapes to temporarily preserve them:

For quite a few years now, I've worried about, and mentioned here, the panic and depression that sets in once you experience your original Dolby Master tapes turning into PTS (Pure Tree Sap!) It's by now a very well known condition, and some of you have gone through the debacle. I'd like to thank those of you wrote me and explained that there are several steps you can take to restore (albeit only temporarily) these tapes to playable condition. Gives one time to make a few very clean copies, so that if the master continues to croak, at least you'll have these protection copies. [...] Many of you well know all of this. A trick which took a while to discover, was to bake the affected tapes gently in a controlled "oven" of some kind, for a few hours, enough to drive off the water, and allow many of the molecules to migrate back where they belong. You also must allow the tapes to cool back down slowly, or water gets reabsorbed. And you can't use a gas oven, which generates steam molecules in the warm air (if it also doesn''t wreck your tapes from uneven heating!) The back coating was affected in similar ways, on tapes that used this well-intended bad idea. This coating is also made somewhat more stable by the slow heating and cooling process.

http://www.wendycarlos.com/newsold.html?mc_cid=c30e91181a&mc_eid=d8caa171eb#baketape

6 - https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Data_degradation

7 - I created GitGhost to backup my Ghost blog for this reason: https://github.com/sharedphysics/GitGhost

9 - https://www.wired.com/2012/11/google-spanner-time/

10 - https://news.microsoft.com/innovation-stories/project-natick-underwater-datacenter/

11 - https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2016/06/can-neuroscience-understand-donkey-kong-let-alone-a-brain/485177/ and also https://journals.plos.org/ploscompbiol/article?id=10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005268 "Could a Neuroscientist Understand a Microprocessor?"

12 - https://www.npr.org/templates/story/story.php?storyId=89380697

14 - https://voyager.jpl.nasa.gov/golden-record/

Related is the search for a "10,000-year symbol" for radioactivity, something clear enough that could be unambiguously decoded as deadly long after the original creators and generations are forgotten: https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20200731-how-to-build-a-nuclear-warning-for-10000-years-time

Also related are the 10,000 year clock by the Foundation of the Long Now, and the tragi-comedy "A Canticle for Leibowitz" about the rebuilding of knowledge and civilization after nuclear war from fragments that survived and from first principles.

Thanks for reading

Useful? Interesting? Have something to add? Shoot me a note at roman@sharedphysics.com. I love getting email and chatting with readers.

You can also sign up for irregular emails and RSS updates when I post something new.

Who am I?

I'm Roman Kudryashov -- I help healthcare companies solve challenging problems through software development and process design. My longer background is here and I keep track of some of my side projects here.

Stay true,

Roman