I have a two year old, which means I’ve been reading a lot of stories with some morality or lesson baked into them. And the thing that bothers me is that the lessons are often wrong.

Consider the story of the tortoise and the hare.

You know the one: a tortoise and a hare have a race. Hare is way ahead, decides to take a break. Falls asleep. Tortoise eventually catches up and crosses the finish line first.

Here’s the full story:

A Hare was making fun of the Tortoise one day for being so slow.

"Do you ever get anywhere?" he asked with a mocking laugh.

"Yes," replied the Tortoise, "and I get there sooner than you think. I'll run you a race and prove it."

The Hare was much amused at the idea of running a race with the Tortoise, but for the fun of the thing he agreed. So the Fox, who had consented to act as judge, marked the distance and started the runners off.

The Hare was soon far out of sight, and to make the Tortoise feel very deeply how ridiculous it was for him to try a race with a Hare, he lay down beside the course to take a nap until the Tortoise should catch up.

The Tortoise meanwhile kept going slowly but steadily, and, after a time, passed the place where the Hare was sleeping. But the Hare slept on very peacefully; and when at last he did wake up, the Tortoise was near the goal. The Hare now ran his swiftest, but he could not overtake the Tortoise in time.

They tell you the lesson is “slow and steady wins the race,” which is a great metaphor for grind and persistence, a useful adage, and so on.

But that’s the lesson for the tortoise. And in ninety-nine out of a hundred other versions of that story, where the hare doesn’t stop and just finishes the race, the tortoise loses. Because the tortoise is slow and the hare is fast. No amount of going slowly and steadily is going to help the tortoise win. The tortoise wins not because of its virtue but because of the unforced mistake of the hare.

I can come up with seven different lessons off the top of my head. How about:

- “Don’t rest in the middle of a race.”

- “Give your best no matter who you’re competing against.”

- “Wait for your competitor to make a mistake, then exploit it.”

- “Avoid making unforced errors.”

- “Celebrate only after winning.”

- “Don't abandon your competitive advantage.”

- “Only challenge stronger competitors who have exploitable weaknesses.”

In fact, the original Aesop version has it as “The race does not always go to the swiftest,” which is very different. (I’ve also seen a religious reading that pulls out “Pride comes before the fall.”)

There's much more for the hare to learn than for the tortoise. And “Slow and steady wins the race” is not only the least statistically likely lesson, it’s also probably the more boring one.

So the lesson changes depending on whose perspective you take. If you're the hare, you learn a different lesson from that interaction than if you're the tortoise. Moreover, the lesson that is learned may be extremely context specific.

Let’s run the fable past its original ending: the tortoise wins the first race and learns that “slow and steady wins the race.” The hare learns “don't abandon your competitive advantage.” (Don’t rest in the middle of a race).

At some point, the hare and the tortoise have a rematch. The hare trounces the tortoise. They’re not even in the same league. The hare does not go slow and steady, the hare goes fast and pushes as hard as it can and then gets to the finish line and takes a nap. The hare goes on to race against and beat other animals. It focuses on short and middle distance lengths, optimizing for fast-twitch muscles and avoiding underperforming in long races. Eventually the hare retires as the undisputed greatest. Meanwhile, the tortoise continues to race but never finishes in the top quartile again. The tortoise justifies it by saying it is a marathon, not a sprint, that it is doing it for personal development, but it never wins another footrace.

Eventually the tortoise learns that it is playing the wrong game. It is not optimized for foot races, though it originally might have gotten the opposite impression for a highly luck-dependent N-of-1. It moves into swimming long distances, which is a more natural fit.

Eventually, in their old ages, the tortoise and the hare let bygones be bygones and have a rematch. They race by the beach. The tortoise climbs into the water and swims; the hare hops across rocks in the shallows. They reach the end neck and neck.

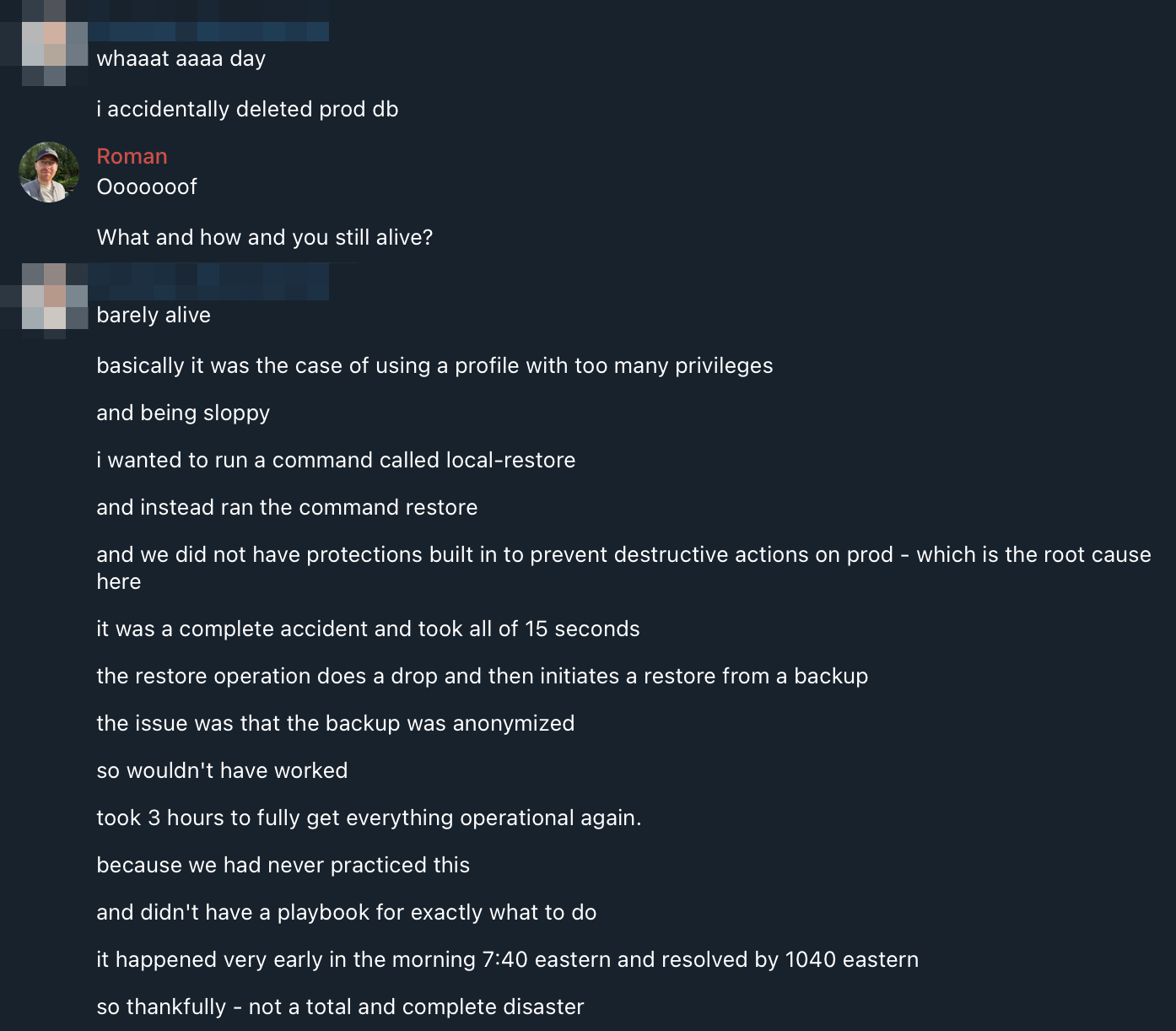

A friend of mine recently dropped his company’s production database by accident. Instead of running a local drop command, he did it to prod instead. The command had no failsafe and took seconds to start and drop. Turns out the company had never done a restore from backup exercise and it took 3 hours to restore services.

He happened to be in an EU time zone working for an American company focused on education tools, meaning that his entire ordeal was early enough in the morning that it never affected end users and the data loss was negligible.

After the retrospective, they implemented a new multi-step process. You have to manually confirm which environment you are working in. There’s a big new “Danger” and confirmation step when you run the command, can’t miss it. They also set up code red drills to practice recovering from emergencies like that.

I can imagine the manager now: “And what lesson did we learn from all this?”

Well, it depends. How about, “Mistakes that don’t affect users are forgivable.” Or: “We should actually practice those best practices, not just wink-wink-nudge-nudge agree that yes, we should really run those code red drills, but it's so unlikely to happen here that we've deferred them indefinitely.” Or if you’re a security guy, “Implement two-key critical processes!” Or if you’re my friend, “Always double check where you are working.”

There are fifty lessons here, each dependent on perspective, each with different utility and reproducibility. But one of the cardinal sins of software engineering is to generalize from a single instance. Was this an exception or was this an inevitability just waiting in the wings if given enough engineers and time?

Sometimes things that are very unlikely to happen, do happen. And sometimes things that are very likely to happen, don’t.

This reminds me of the story about bomber planes during WW2. A group of bombers would fly out on a mission, but not all of them would return. The ones that did had bullet holes concentrated in the wings. The military's instinct was to reinforce the wings on all their bombers, but this seemed wrong — survivability wasn't improving.

Statistician Abraham Wald, working at a secret research group in Columbia University, realized the accepted wisdom was backwards: this was survivorship bias. They needed to consider the planes that didn’t come back, which led to the insight that the wings don’t matter, but damage to the engine and cockpit is fatal. When those were reinforced, survival rates improved.

Survivorship bias! What a nice statistical term to describe lessons learned and broadly generalized from a particularly uncommon outcome.

“Reinforcing the wings” reminds me of another famous story, of Icarus and his father Daedalus.

Most versions of the story have them escaping from an island by having Daedalus make wings for them out of molted feathers, beeswax, and threads from old sheets. Daedalus tells Icarus “not to fly too low or the water would soak the feathers and not to fly too close to the sun or the heat would melt the wax.” Icarus memorably ignores these instructions, flies too high, melts the beeswax, and plummets into the water where he drowns.

This is where the idiom around “those who fly too close to the sun…” comes from, but if Icarus had flown too low, the idiom we would have been left with would have been “don't fly too close to the water.”

From all this, Daedalus did not learn anything new – he already knew the risks, which is why he warned Icarus. And whatever Icarus learned, it had a very short utility as he plunged into the sea and died.

So perhaps the lesson should have been, "Kids won't listen to you, so don't set them up to fail by designing escape plans that require compliance in high-risk situations". Or, “It’s better to fly at night.” Or, “Do a better job on the wings.” Or, “Don’t try to be too clever; build a boat when you're trying to get off an island.”

Perhaps learning lessons from a story – or from history – is not the point.

History – and most stories – are context-specific. The number of things that have to go right for something to have happened the way it did are often immeasurable. That's context. History and its stories are shaped by that context and cannot be separated from it. It’s hard to point at a story and say with some definitiveness whether the way things went were due to luck, circumstance, willpower, or inevitability. It’s also impossible to recreate the initial conditions and subsequent actions that led to the outcome. After all, we can’t rerun history with different variables to tease out which ones mattered.

At best, you can describe what happened. But even that is reductive — we simplify the retelling of things by choosing what to include and what to leave out. In simplifying the world, we make it possible to tell stories about it. But choosing the simplifications is an act of bias, and a decade later someone will come along with a revisionist view of the world, choosing different details for the retelling, and subsequently drawing different lessons from it.

The lessons we draw from these stories are just pithy descriptions of the punchline. “Slow and steady wins the race” describes what happened one day when a tortoise challenged an overconfident hare to a run. “Don’t fly too close to the sun“ does the same for Icarus’s brief and exuberant escape. These lessons are also fragile — had the outcome of the story been different (all other things similar), so would the lesson have been different. And so the lesson — the thing generalized as an instruction to “do this, not that” — isn’t even connected to the rest of the story.

Here’s a game I like to play: whenever I read stories about exceptional people or exceptional situations, I look for counterfactuals to whatever takeaway the writer is pushing. For every example of privileged success, there is someone who came from nothing. For every example of victory from following a tight playbook, there is someone just as effective who did not know there was a playbook, let alone followed it.

Let’s say we’re reading about renaissance painters. Leonardo was an illegitimate son of a notary who apprenticed in one of the best schools of art during the renaissance. His workshop contemporaries were Lorenzo di Credi, who painted competent religious works and is mainly remembered as “the guy who trained with Leonardo.” There was Perugino, who became successful and respectable and then was totally eclipsed by his student, Raphael. Raphael himself came from a life of privilege, ran in Vatican circles, and died young with a reputation as one of the greats. Raphael’s father, Giovanni Santi, was a court painter with all the same connections but ended up as a footnote in reference to his son. Or take Caravaggio—orphaned at eleven, likely illiterate, arrested multiple times for brawling, killed a man and fled Rome with a price on his head. He also died famous, revolutionized painting, and changed art history.

What do we learn from these stories, these different lives with converging endpoints and similar lives with diverging endpoints? Is there some grand truth to pull out of biography that we can apply broadly and with certainty?

No. There is no grand truth, no repeatable instruction for how to become a Leonardo or to raise a Raphael. (If there was, it would be widely exploited). They are just stories and cases. A successful artist can look like this, but they can also look like that. Even in their exceptional outcomes, they differ: Leonardo was a polymath; Raphael was a painter and architect; Caravaggio was a painter. What was true for one of them was not true for another; some variables may be better predictors of future success, but none guarantee outcomes. Sometimes what truly matters is luck-dependent, like meeting the right collaborator or being born into the right family or era. We can certainly continue to dig deeper — we can pathologize, we can probe into more specific biographical details, turning points, and communities they ran in. But for each fact there is a counterfact represented by one of their contemporaries. Their lives are their own unique cases. Their lives are not the lives of others, and never will be. Their lives are not your life.

So there are no lessons to be learned, no instructions or certainty to pull from history and from stories. Or rather, learning lessons is not the point. Narratives and stories have their place. They entertain and they communicate valuable details — context — about the world.

But when it comes to learning, the goal is not to take a story — a simplified world — and to generalize it to represent an instruction that when followed will ensure repeatable outcomes.

The alternative to trying to pull certainty from a story is to instead look at stories as cases for pattern recognition rather than actionable lessons. A single story can be illustrative of many different concepts, and a single idea can manifest in the world in many different ways. It is to hear the story and remark, “Wow. I’m filing this one under ’overconfidence’, or ‘varieties of success’, or ‘what fake it till you make it looks like’.”

Eventually, you build up a repository of stories to reference. You can look at things happening and say, “This situation looks a bit like these other things I read about. In some of those stories, people did this and got one result; in others, they did something else.” Such pattern recognition is your compass for navigating the uncertainty and complexity of the world: not because it tells you what to do, but because you've seen a range of what's possible.

Reading for lessons is how we see a race between a tortoise and the hare and conclude: “I should work steadily and persistently,” when a better reading may be that “this is a case where overconfidence led to unforced error, where playing to your strengths matters, where cause and effect seem to have been flipped and where a single lucky outcome has created a misleading narrative. I can work with that.”

The world is complex. The world is a mess of detail that rarely looks the same. It changes, it accumulates. The world contains multitudes. Of course it’s our prerogative to try to impose order and certainty upon it, seeking comfort in some absolute instead of grappling with the inherent relativity and reflexivity. But the world is too big to wrap our hands around, too complex for any single framework to capture or describe. (And efforts to impose order on the world bring about their own complications and unintended reactions). Let’s not confuse what we want — lessons, certainty, a playbook to follow — with the reality that we move through.

Things can take many forms. Two people, looking from different points in life, will see different things in your story, and perhaps the same thing in different stories.

Oh, and this essay, this collection of anecdotes, also has no lesson. It’s a remark, to be filed away, and hopefully one day be useful.

Thanks for reading

Useful? Interesting? Have something to add? Shoot me a note at roman@sharedphysics.com. I love getting email and chatting with readers.

You can also sign up for irregular emails and RSS updates when I post something new.

Who am I?

I'm Roman Kudryashov -- I help healthcare companies solve challenging problems through software development and process design. My longer background is here and I keep track of some of my side projects here.

Stay true,

Roman